Some of the mahi we have planned

Building resilience is nothing new at Waikato Regional Council where environmental, scientific, policy and technical experts work every day managing flood protection infrastructure, generating and making sense of up-to-date data information, protecting and restoring environmental resources, planning transport networks, and so much more.

We thought you might be interested in their work, so we gathered a few of them to share their stories about some of the mahi (work) we have planned over the next 10 years to support the region and its resilience.

Financial resilience

We’re not like district, city or unitary councils that provide more visible and direct services to their communities.

We’re more like the quiet achiever that quietly beavers around in the background for long term gains across our region and also nationwide.

A lot of the work we do is long term and focused on future effect and not something we’d just stop doing: routine monitoring to support future decision making about resource use or the environment, supporting our biodiversity and biosecurity, building more resilient communities in the face of climate change and natural disasters …

But with new government regulations, increasing prices and a cost-of-living crisis that’s very real for our communities, our elected members were quite clear that we needed to keep our rates at an affordable level.

With this financial resilience in mind - balancing affordability today with managing for the long term - we’re making sure we continue to deliver what’s important for our region in the long term without shying away from some of the big challenges we face.

Therefore, we’re investing in some short-term strategic actions that will set the platform for the future. This includes developing a water security management plan, reviewing how we fund critical infrastructure, furthering our understanding of this region’s natural hazard and climate risks to enable resilient decision-making, and identifying actions to rehabilitate the degraded catchments of Lake Waikare and Whangamarino Wetland.

Janine Becker, Finance and Business Services Director

Te ao Māori

Kia kaha, kia maia, kia manawanui. Be strong, be brave, be steadfast.

This whakatauki emphasises the importance of resilience and determination in overcoming obstacles in adversity.

Resilience from a te ao Māori perspective encompasses a deep and holistic connection to whakapapa (genealogy), whenua (land) and whānau (family). It's these concepts that provide a foundation of strength and support during challenging times.

Waikato Regional Council is very much about embracing Māori values in everything we do. In fact, we have an obligation to involve iwi Māori in all the things that we do.

Our strategic priorities – water, the coastal and marine areas, our biodiversity, connecting with others, our climate – are very much aligned to what is important to iwi Māori. We can learn much from listening to the wisdom that Māori can bring.

Our iwi capacity programme, Te Hōtaka Manaaki, is our way of saying to iwi Māori, let's work together and make things better. Through this programme, we are able to resource iwi Māori in a way that they are better able to engage with us so that the iwi Māori voice is heard and respected.

And together, we can work towards building a future where everyone can thrive and be more resilient.

Mali Ahipene, Pou Tūhono

Biodiversity and biosecurity

If we manage our growth and natural resources well, we’ll get better outcomes on the ground: more birds, more leaves on trees, more fish, fewer invasive species.

This will lead to more resilient ecosystems that can then deal with increased severity of events like flood and drought; this is known as better ecosystem services.

Our biosecurity programmes save money and make us more resilient in the long term. As an example, alligator weed has quite a limited distribution in the Waikato because we’re holding the line, but left unchecked it has the ability to cause chaos. It’s a really toxic plant. It can kill stock and choke wetlands and rivers.

Investment now will save our communities angst later on. And there are loads of pest plants like that, and pest animals. All of which have an impact on biodiversity.

We’re looking to empower more communities to take ownership of the biodiversity they care about. We know they care and they want to be proactive, so we are proposing to increase our funding and support.

When it comes to restoring the natural environment, our communities really get their own issues.

Patrick Whaley, Biosecurity and Biodiversity Manager

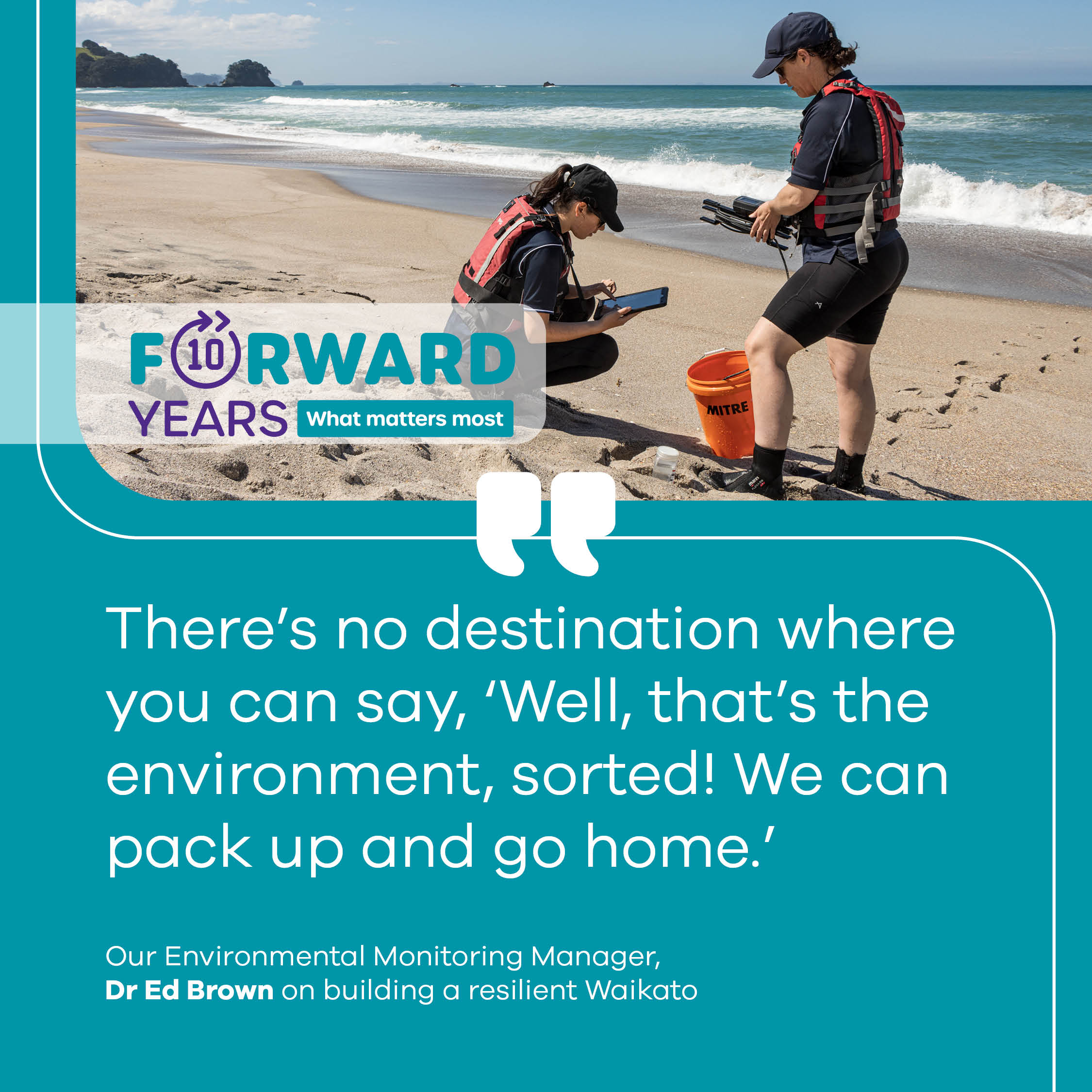

Environmental monitoring

A large part of what we do is build a collective knowledge base that can help decision makers, both in the council and within other parts of the community.

If we understand things better, we can collectively manage things better on behalf of the region and be confident that good sound decisions are being made.

We have teams that gather, analyse, interpret and translate information on the Waikato’s natural resources, communities and economy. The information is future-focused, so it enables us to respond to emerging issues and new challenges.

Last year, we brought together an enormous amount of information collected over decades on the state of the environment. What was highlighted was that we know a lot about things like freshwater quality and quantity but there are whole lot of parts of what’s happening in the environment that we need to know better, so we’ll be expanding our routine monitoring programme.

We know that the region’s population is going to continue to grow and keep putting pressure on our natural resources. There’s never an end point to this work.

There’s no destination where you can say, ‘Well, that’s the environment, sorted! We can pull back up and go home.’ It’s an ongoing journey.

Dr Ed Brown, Environmental Monitoring Manager

Lakes and wetlands

Many of our shallow lakes and estuarine areas have been under pressure for a long time and are often really degraded, but we can do something about that.

Lake Waikare and Whangamarino wetland are an example of where a system has flipped. The environment has become so degraded that we’re dealing with fish kills and bird kills when periodic storm events or drought occur, largely driven by climate. With stakeholders, we’ll be coming up with a range of management options to help build resilience in the system, particularly around making sure populations of tuna and waterfowl are maintained.

However, we also need to recognise that it’s within a landscape that’s highly controlled in terms of the Lower Waikato Flood Protection Scheme and the productive land it protects. So, we’re trying to come up with options to improve the environmental outcomes, while also providing for those other values.

That’s a really difficult balance and we know we can do better.

Dr Mike Scarsbrook, Environmental Science Manager

Critical infrastructure

The sustainability and affordability of our flood schemes are very real issues for us and for the communities our assets protect.

Our schemes are aging and coming up for renewal at almost the same time. They were established decades ago under very different times.

It’s very clear that our flood schemes need to keep up with changing regulation, land use and geological processes. We need to consider existing infrastructure and levels of service alongside the health of our wetlands, safe fish passage and looking towards more nature-based solutions where feasible.

Climate change is also testing the levels of protection that our assets provide.

So there’s a real challenge for us to try and work out what’s the right thing to do in the right place and at the right time. The cost of maintaining or building new infrastructure has also risen significantly, which means we need to look differently at how we fund our flood and drainage schemes into the future.

Adam Munro, Flood Protection and Land Drainage Manager

Natural hazard risk

Increasing community resilience to natural hazards means understanding the system and working with communities on the risks so they’re empowered to make the right decisions.

Every community is different with regards to the physical environment and the risks they may face; and every community has a range of dynamics that we need to understand, like what are their economic, social, cultural and environmental values and how they are all linked, interconnected?

Once we know all that, we can begin to understand what resilience means for a particular community and what course we should steer together to manage their risks for the future.

Rick Liefting, Regional Resilience Team Leader

Coastal and marine

Our marine systems face multiple and cumulative stresses.

We’ve focused a lot on estuaries as the interface between catchment activities, fresh water and the marine environment, but we recognise there are effects further offshore.

So we’ll look more broadly at the ecological health of our coastal marine area and we’ll see the inextricable links between biodiversity and resilience, including rocky-reef ecosystems.

We know that some of these lack resilience; a kina barren is a good visual example. These areas are bare because kina have proliferated due to a lack of predators and they in turn devour kelp faster than it can grow.

Looking at biodiversity, ecosystem health and habitat coverage will generate a lot of baseline information that, in time, will help us assess how resilient our systems are and whether they are changing.

We’ll continue to strengthen monitoring systems across the Firth of Thames, which has been classified as a degraded waterbody. This monitoring will check that it doesn't degrade further and hopefully capture its recovery.

We will also focus more on water quality and developing quantitative standards for policy. This will help provide a mountains-to-the-sea perspective and allow us to keep the marine environment in the best state possible, supporting its resilience.

Dr Michael Townsend, Coastal and Marine Science Team Leader

Public transport

We face two different issues building resilient public transport in the Waikato.

In the metro area and the north, it's all about growth, growth pressures, access to schools, hospitals and other services, and cost of living issues mean more and more people want cheaper alternatives to owning a car and driving their families around.

Outside the metro area in more rural communities, the key difficulties are around accessing specialist health or educational services that tend to be centralised. These locations are harder to serve with public transport and people may instead rely on community transport which we provide grants towards.

A good example of more regional rural need is the Te Kūiti Connector. We launched that service because many students in the south of the region around Te Kūiti were unable to carry on training at Wintec without a public transport service to Hamilton. But seven funders had to be herded together to deliver one bus, and we rely on them all staying on board for it to work.

So the big move for public transport resilience in this LTP is changing to a regional ratings model. If we controlled the available funding, we can do the long-term planning and design and cost our future network through the LTP and Regional Public Transport Plan consultation, avoiding a longer process with lots of councils.

At the moment, we only rate in Hamilton, Matamata-Piako, Thames-Coromandel and Hauraki and have no control over funding outside those areas. If the other districts want to spend money on public transport, they'll spend money on public transport; if they don't, they stop and we have to stop public transport services. So it's not an ideal situation, particularly if we have put a lot of effort into starting a service.

That’s why a regional rate for public transport would be a game changer if it’s supported through consultation. We would be able to show the service options, costs and impact on ratings all in place.

Sarah Loynes, Transport Policy and Programmes Manager

Water security

Our economy has grown in a time where there’s been no water scarcity.

Now, because demand has increased and supply has decreased, we’ve ended up in a place where our economy needs to adapt to the change in situation.

We have seen a trend of decreasing rainfall across the Waikato since the 1960s, so we don’t have the wealth of water we once had. Often, much of the rain is now falling in more intense bursts and less regularly.

Dealing with water security is a key issue in terms of regional resilience because if we are to continue to grow and prosper, we’re going to have to deal with our water security issue.

Part of that is understanding how much water we have, how it’s being used and how we can use it much more effectively and efficiently. So, it’s both demand and supply.

Dr Mike Scarsbrook, Environmental Science Manager

To ask for help or report a problem, contact us

Tell us how we can improve the information on this page. (optional)