Waikato Regional Council has started a pilot terrestrial biodiversity monitoring programme on private land to help give an overview of the state of indigenous biodiversity across the region and drive improvements in biodiversity management and policy

Dr Liz Overdyck reads the slope of the site with a digital inclinometer.

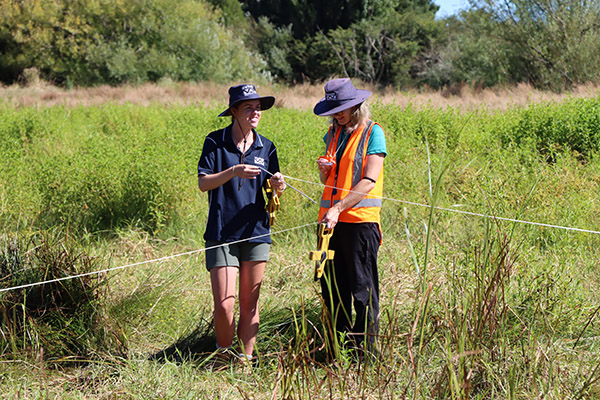

Summer student Ayla Vette and ecology scientist Dr Liz Overdyck set up a corner of the monitoring plot.

A remnant of kahikatea trees make up part of the wetland area of a monitoring site located in Waihou.

Ayla Vette sets up a chew card along the 200 metre long transect out to an acoustic bird recorder.

When the end of a 200m transect takes you into a muddy pond.

The use of a standard methodology and sampling regime means that data collected is comparable across private and public land.

Walk a straight line for 200 metres, setting down a possum chew card at every 20 metres. Through waist-high reeds and rushes you go, and mind that muddy creek. Climb through a wire fence, part thick, scratchy, weedy scrub to enter a kahikatea stand, clamber up and over fallen trees, wade through thick tradescantia, and crawl under another wire fence. With about 30 metres left to go, turn 90 degrees at the Waihou River because you cannot cross it and, botheration, that means going straight into a stagnant muddy pond. But in there you must go to set your acoustic bird recorder.

Waikato Regional Council is trialling a pilot terrestrial biodiversity monitoring programme on private land in the hope that a full monitoring programme will one day give an overview of the state of indigenous biodiversity across the region, and drive improvements in biodiversity management and policy, both locally and nationally.

“The Department of Conservation reports on the state of native biodiversity on public conservation land, but we have only scattered evidence of what’s happening across the rest of the country,” says Waikato Regional Council Terrestrial Ecology Scientist Dr Elizabeth Overdyck.

“As a council, we do work with community groups and individual landowners who are undertaking ecological restoration projects but having a comprehensive biodiversity monitoring programme in place would enable a a complete picture about what is happening in the biodiversity space right across the whole region.”

Reporting on the state of the environment is a role of regional council. The councils, along with the Department of Conservation (DOC) and Crown Research Institutes, contribute to regular national state of environment reporting.

“New Zealand also has international responsibilities for biodiversity monitoring and reporting under the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, which our work feeds into,” says Dr Overdyck.

“However, while a lot of the monitoring we do as a council is understandably focused on the state of fresh water and the ecology of fresh water, we need to increase information being gathered about the terrestrial and coastal side of things – including wetlands where we have the crossover between water and land ecosystems.”

The pilot terrestrial biodiversity monitoring programme is visiting a small sample of sites from a proposed five-year programme to collect baseline data for vegetation, birds, bats and pest mammals and plants at 286 survey plots on private land in the Waikato. If a full monitoring programme can be resourced, sites would be revisited on a five or 10-year cycle to establish long-term trends in biodiversity for the region.

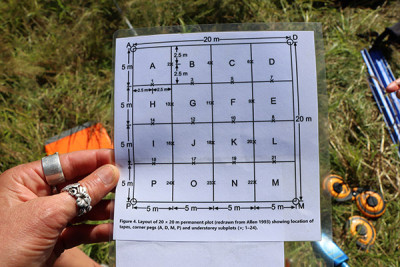

The trial has adopted a strict 8-kilometre grid and methodology already being used nationally by DOC, Ministry for the Environment and several other regional councils. The use of a standard methodology and sampling regime means that data collected is comparable across private and public land.

“We’re testing the methodology to see if it captures data that is useful to us and which provides a good representation of what’s happening across our region, both as a snapshot in time and in detecting long-term changes,” says Dr Overdyck.

A 20-metre by 20-metre monitoring plot with quadrants and corresponding transect lines are set up at each site. Markers will be buried to ensure the exact same site is monitored in the future.

Dr Overdyck and her team then survey for the presence of vegetation, birds, bats, possums, rabbits, hares, and ungulates. Other incidental sightings of interest are also recorded.

“We spend two days at one site,” says Dr Overdyck.

“The first day is spent setting up, measuring vegetation, and counting pellets for rabbits, hares, goats, deer. The second day we do five-minute bird counts and gather in all the data from acoustic recorders and possum chew cards.”

Seven sites across the Waikato have been completed so far, and each have yielded quite different results.

At the latest site, next to the Waihou River, the landowner had seen bittern and white heron on the property, while the introduced Eastern rosella could be heard calling and Honshu white admiral butterflies – biocontrol agents that target the pest plant Japanese honey suckle – were flying about.

“There has been the assumption there is nothing much of interest on private land but there are a lot of rare ecosystems that occur in the lowlands, away from public conservation land, like wetlands and remnant forest patches,” says Liz.

“While many of the sites we have visited so far are in pasture, we have been pleasantly surprised by what we’ve seen. One paddock had 43 species of plants, and we’ve seen kākā fly overhead at two sites already.

“One of the sites we turned up at was a maize paddock, so the vegetation count there was pretty easy. But this information can still be useful when we look at the corresponding animal data and as a starting point when we don’t know what surrounding land use change may hold for future biodiversity.

“Biodiversity doesn’t just occur on public conservation land, and we are finding that landowners are genuinely interested in being involved in this monitoring programme and contributing to a better regional and national picture of biodiversity.”