- Waikato fresh water facts •

- Check the water alert level with your local council •

- What happens if too much water is taken? •

- All that water! What’s the problem? •

- Small leaks in pipes – BIG water losses •

- Water - where does it go when we're done with it? •

- Getting the water to you – it’s not cheap and it’s not easy! •

- Treating the water that comes from rivers and streams •

- Tour of the Hamilton City Council water treatment plant

Waikato fresh water facts

Our region has more than 100 lakes, over 20 rivers, about 1,400 streams and many underground aquifers. We've also got the country's longest river and largest lake.

It's easy to wonder why we need to conserve water.

But they all need to provide fresh water for agriculture, industry, power generation and, of course, water for use at home.

And our recent summer droughts are a strong reminder that we can’t take our freshwater resources for granted.

- About 75 per cent of people in the region live in urban areas.

- About 65 per cent of water used is taken from rivers and streams.

- About half the region's rural population relies on groundwater for drinking.

What happens if too much water is taken?

Our rivers and streams suffer

- Water levels and flow patterns – like riffles and pools – will change, altering the condition for life there. In extreme conditions, small watercourses could run dry.

- The temperature of water is likely to rise and harm fish, plants and other aquatic life. Higher temperatures also limit the use of water for industrial cooling.

- There may be a higher concentration of pollutants like silt and nutrients, causing algae to grow.

- These changes may affect the cultural value of the water body as a food source and for its own life essence (mauri). Recreational uses, like fly fishing and kayaking, may also be at risk.

Our groundwater is affected

- The flow to springs, streams and rivers can be reduced.

- Neighbouring wells can be affected.

- Levels can decline over the long term, reducing the availability of water for future generations.

- Over extracting from coastal aquifers increases the risk of saltwater being drawn into the fresh water reserves. This can make them permanently unsuitable for drinking and many other uses.

All that water! What’s the problem?

While municipal water returned to the river is treated to a high standard, water from a number of other sources remains a problem. These include run-off in urban areas (oil on roads, for example) and from rural and forestry land. Maintaining high water levels and volumes helps dilute the contaminant load entering the water bodies and assists in maintaining water quality.

So, small efforts around the home and at work to conserve water all add up. If we all do our part, it makes a difference.

There are many ways we can conserve water during the summer months. Read on to find out how!

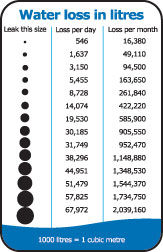

Small leaks in pipes – BIG water losses

Underground water lines on residential properties are subject to breaks and leakage. Whether you’re on a large property in the country or a section in town, a leaking water line can lose a massive amount of water if it’s not repaired promptly.

Underground water lines on residential properties are subject to breaks and leakage. Whether you’re on a large property in the country or a section in town, a leaking water line can lose a massive amount of water if it’s not repaired promptly.

The chart to the right shows just how much water can be lost – about 14,000 litres a day, for example, through a hole the size of a small nail.

With a water meter, it’s easy to do an overnight check for problems. Just read the meter before going to bed, then first thing in the morning. The difference should be minimal.

Watching for leaks if you don’t have a meter is a little trickier. To do it, follow these tips:

- Confirm the path of your water line from the edge of your property to the house. This is usually a direct line from your water toby (tap) at the property boundary to the outside tap in the front of the house.

- Watch for wet spots on dry ground (there could be water soaking the ground from the line below) or for grass areas that grow more quickly than others.

- Sometimes you can hear the water rushing out of the pipe, so keep an ear to the ground!

Small leaks lead to big water losses very quickly! So keeping an eye out – and that ear to the ground – can make a real difference.

Water - where does it go when we're done with it?

So where does the water go once we’ve used it and it disappears down the plughole?

When we flush our toilets, drain our baths, showers and sinks, and use the dishwasher or washing machine, the wastewater is carried through a network of pipes to a treatment plant. This is good service for town and city residents! (If you’re on rural property, used water goes to either a septic tank or drainage field.)

The contaminated wastewater (also called sewage) will contain a small amount of solids, including dissolved detergents and chemicals, food scraps, human waste and other small bits of rubbish. It also includes bacteria and viruses that can make people ill.

Councils treat wastewater, first by screening out any solids, then treating it to a level that meets requirements of the discharge consent. Chemicals and energy are used in the process, so any water we conserve at home or work will reduce wastewater flows and save money.

Getting the water to you – it’s not cheap and it’s not easy!

We drink it, cook with it, shower under it, or bathe in it. We use it to wash our dishes, clothes and cars. We might even put it on lawns and gardens to keep them healthy and green. Access to fresh, clean and plentiful drinking water is a cornerstone of modern society!

If you’re on town supply, it’s easy to take water for granted. But it’s no easy task to withdraw it from a source, treat, and deliver it to you the customer. And it’s expensive. Costs for water treatment and supply along with wastewater treatment are significant. This is all in order to meet resource consent requirements and public health standards.

Highly-skilled council staff manage and operate treatment plants, storage reservoirs and distribution pipelines (networks), so when you turn on the tap the water’s there.

Treating the water that comes from rivers and streams

From source to tap:

- Intake. Water taken from the source is screened to keep out fish, plants and leaves before it enters the treatment plant.

- Chemicals added. Chlorine, alum and other chemicals are added to the water to kill germs, improve taste and odour, and start to settle solids in the water.

- Sedimentation. The water enters sedimentation tanks where the chemicals added mix together so there is further settling and small particles are removed.

- Filtration. The water then passes through filters (usually layers of sand and gravel), which remove any remaining particles.

- Disinfection. A small amount of disinfecting chemical (usually chlorine) is added to the water to kill any remaining germs and keep the water safe as it travels through the network to the customer.

- Storage. Water can be stored in a closed tank or reservoir before it flows into the distribution system.

- Delivery. Water travels from storage through large pipes called mains, then on through a line to your property.

For groundwater, the process is much simpler. Screening is done by the soil as water travels to the extraction point and disinfection is usually the only treatment required.

Councils spend money on plant maintenance, chemicals for treatment, and energy if pumping is required – such as delivering it to higher areas. Every effort you make to conserve water will help control these costs.